In the introduction to Agrarianism in American Literature (1969), M. Thomas Inge identifies key tropes of agrarianism to include religion (farmer reliance upon God and nature), romance (redemption through natural harmonies), and reciprocity (mutuality of healthy rural communities). These elements have long been expressed in art and literature and inform present considerations of rural challenge and environmental sustainability. To others, like novelist-historian Saul Bellow, the rural American experience “has had a long history of overvaluation,” with notions of self-reliance and fairness mixed with considerable unhappiness, alienation, and provincial pride. The ubiquity of people’s familiarity with agrarian scenes, labor, and traditions throughout the world since time immemorial is evident in a wide range of artifacts, art, and literature. This vast realm of evidence has rendered aesthetic interpretations of harvest in greatly varied ways. The longstanding popularity of the harvest theme from ancient to modern times, throughout both East and West, has contributed works that range from sublime to exceedingly hackneyed. Yet these attest in the main to a conviction that beauty, cooperative endeavor, and remedies to cultural and environmental threats are moral imperatives.

Cultural anthropologist J. Katarzyna Dadak-Kozicka observes that since time immemorial harvest “was essentially the purpose of existence,” and that field labors had a latent contemplative and spiritual dimension commemorated through art and ritual. A century ago journalist Alfred Henry Lewis offered a sobering practical corollary: “There are only nine meals between mankind and anarchy.” The unprecedented pace of social change since industrialization has shifted populations from the countryside to cities and distanced human connections to nature. For many generations farm work has required intimate knowledge of natural systems and long hours of hard physical work whether using human, animal, or mechanical power. These demands have fostered improved tillage methods to increase crop yields and ingenious labor-saving inventions. But such developments have inexorably if irregularly distanced populations from their fundamental reliance on the wellbeing of the land.

The term “harvest” has often been invoked as a quaint synonym for agrarian bounty or some distant ingathering of crops. Throughout the course of civilization, however, harvest has determined sufficiency or want, been the subject of endless anxious speculation throughout the seasons, and in many times has been a matter of life or death. “Give us this day our daily bread.” British scholars note significant social dislocation and political instability associated crop failures in England (e.g., 1481-1482, 1555-1556, 1596-1597), which were usually caused by late rains and resulted in yields of less than 50% of normal production. Periodic “harvest dearths” of such magnitude have been a significant factor in human migrations. In modern times nations have established storage facilities and enacted multilateral policies to ensure food supply resiliency. Yet annual harvests remain the heartbeat of national economies in the twenty-first century and are increasingly at risk from climate change, centralization of agribusinesses, and political instability.[1]

In continental and global contexts imperialism originated, and endures, in the quest for the most coveted natural resource—harvested foods. Various ideologies have been formed since ancient times to justify the conquest. Substantial Roman grain ships transported wheat from Egypt, North Africa, and Sicily; medieval European traders tapped the fertile Great Hungarian Plain, Rhine-Mosel Valley, Great Hungarian Plain, and Ukraine’s “Black Earth” district, while rural colonizers in the modern era transformed the American heartland, Argentine pampas, and western plains of Australia’s New South Wales. Populations of many contemporary societies are preoccupied with various commercial and secular endeavors and take a dependable and diverse food supply for granted. But this confidence belies serious risks, and public concern has been expressed in recent sustainability movements and examinations of exploitive geopolitics.

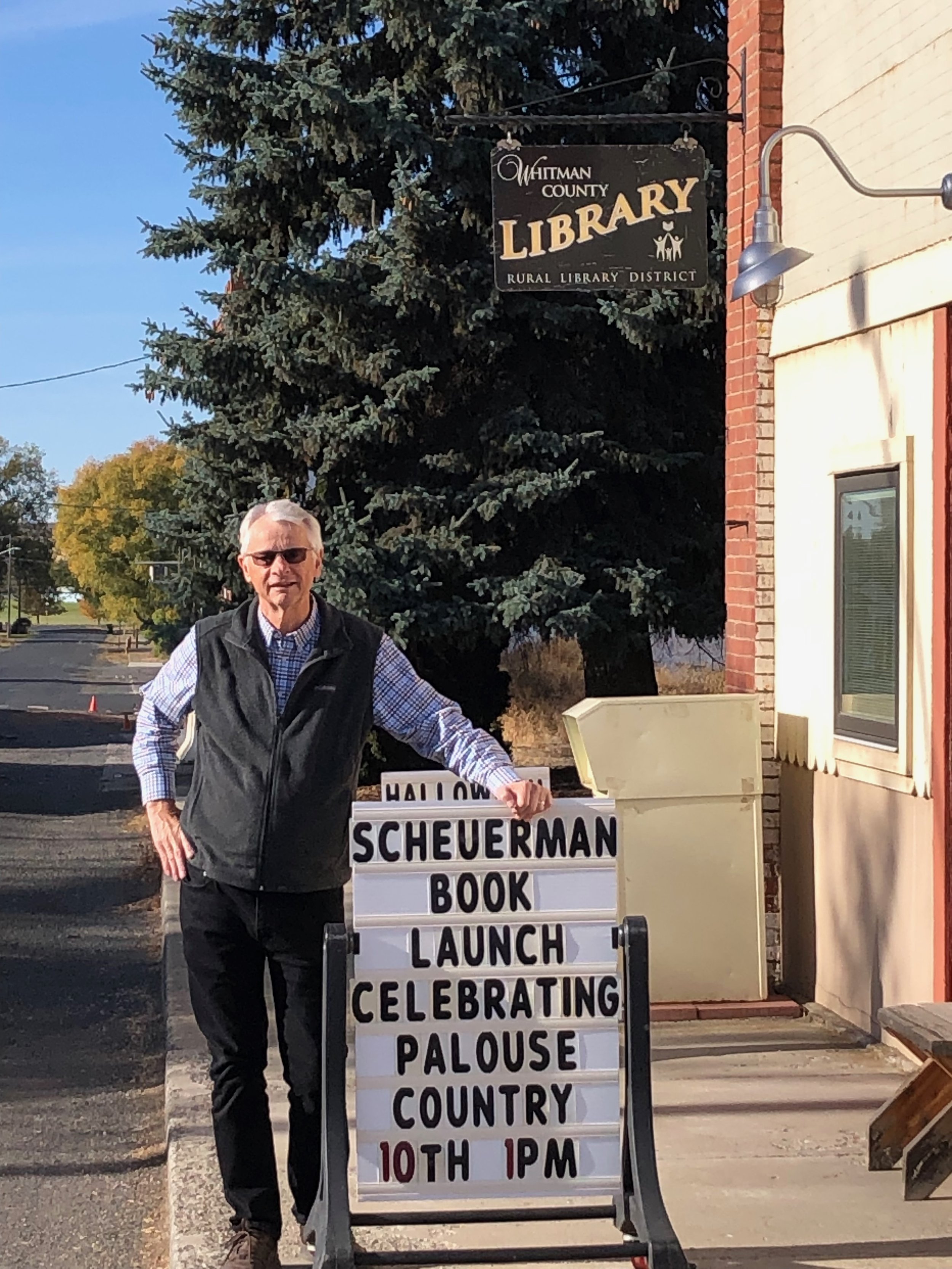

[1] J. Dadak-Kozicka, “Long-sounding Notes and Ornamentation as Characteristic Qualities in Musical Expression in Slavic Harvest Songs,” in P. Dahling, 2009:97. Dadak-Kozicka’s insightful research which observes the distortion of festive and ritual harvest songs by Eastern European socialist regimes after the Second World War is based in part on research described in Eugenia Jagiełło-Łysiowa’s authoritative Elementy Styló Życia Ludności Wiejskiej (Elements of the Lifestyles of the Rural Population, 1978). On the grain trade of the ancient world see Peter Garnsey, Famine and Food in the Graeco-Roman World: Responses to Risk and Crisis, 1989. Concerns regarding modern-day food security due to global warming and geopolitics are explored in Thane Gustafson, Klimat: Russia in the Age of Climate Change (2022), and Karl A. Scheuerman, “Weaponizing Wheat: How Strategic Competition with Russia Could Threaten American Food Security,” Joint Forces Quarterly 111 (October 2023).