The advent of grain foods cannot be dated with precision, but archaeological evidence indicates humans in eastern Africa mixed crushed grain with water to form gruel as early as 100,000 years ago. Cooking on heated stones, with embers, and by other primitive means enabled the roasting and toasting of grains to enhance flavors, but the revolutionary advent of fire-resistant earthenware pots in the Middle East by the eighth millennium BC fostered a significant advancement in human nutrition, culture, and population growth. Grains boiled in water made possible a savory array of pottages, soups, and stews, with the softened food especially benefiting the very young and elderly. No culinary advance since the invention of earthenware has had such a salutary effect on cooking methods.

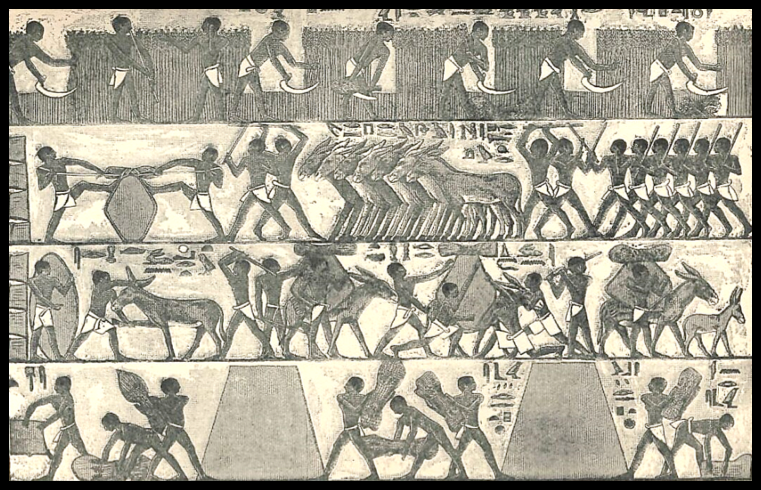

Enduring methods of gathering crops from the Neolithic past to relatively modern times involved use of sickles to cut stands of wheat, barley, and other grains that were harvested at least 10,000 years ago in the Karaca Dağ region of southern Turkey and throughout Mesopotamia. The oldest extant complete sickle, fashioned with sharpened flints about 9,000 years ago and found in the Nahal Hemar Cavenear the Dead Sea in the Jordan Valley, is held by the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. First made of flints embedded into animal jawbones with cypress resin and honey, cast metal sickles began to appear during the Middle Bronze Age about 2,000 BC. The advent of this revolutionary tool helped spur humanity’s agricultural revolution that gave rise to civilizations by providing reliable food supplies and facilitating city life.

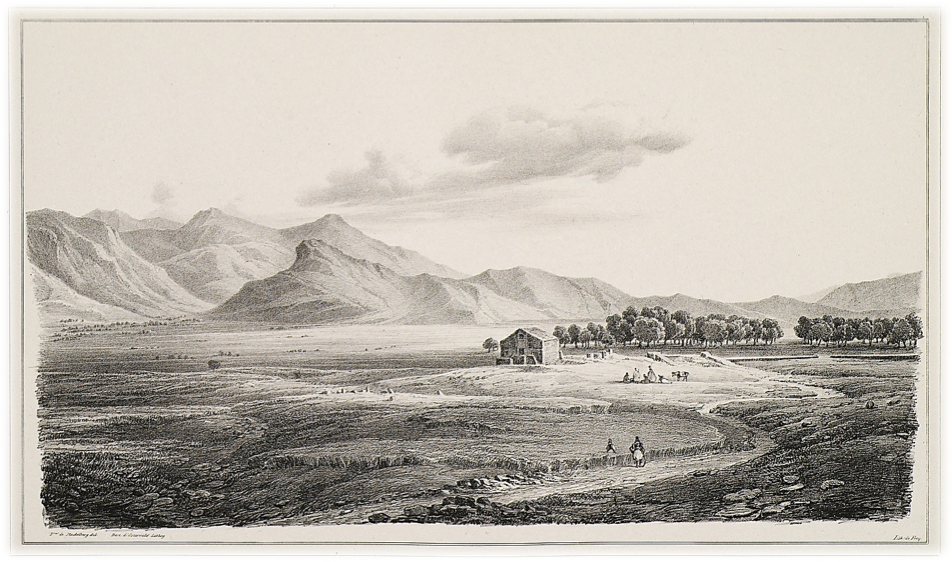

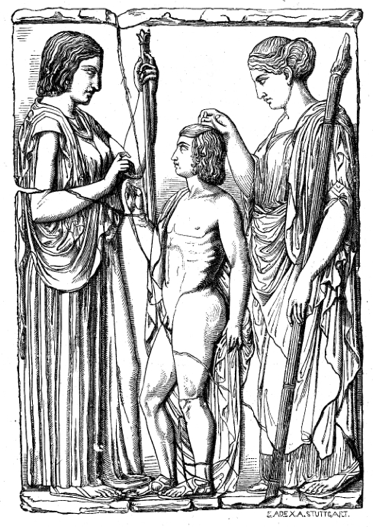

Cultivation of cereal grains has been integral to humanity’s advance since time immemorial. Cereals, named for the Roman goddess of fertility, Ceres, are not only nutritious but also adaptable to a wide range of climates and soil conditions. The ancestral range of modern cereal grains stretched along the Fertile Crescent from the Anatolian slopes of southeastern Turkey—where locals believe Adam first tilled the ground, eastward across the Transcaucasus and Mesopotamia to Kashmir and south to Ethiopia. This vast region is notable for long, hot summers and mild, moist winters which was ideal for the emergence of large-seeded cereals that became the principal foods sources that fueled human expansion throughout the world. The advent of grain cultivation coincided with animal husbandry as villagers sought to prevent creatures of horn and hoof from damaging grain fields by domesticating them. These developments spurred the Neolithic Revolution in Upper Mesopotamia approximately 9000 BC and represented the key breakthrough in civilization leading to food surpluses and the rise of settled, urban populations.

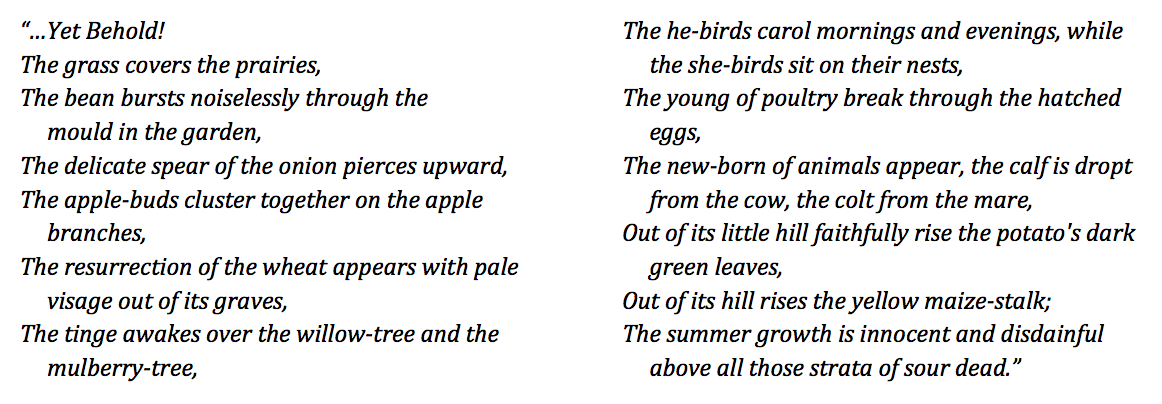

By 5000 BC these primitive self-pollinating plants—capable of evolving more rapidly than any other known organism, had spread along the Mediterranean coast to the Iberian Peninsula and north of the Caucasus Mountains. Some two thousand years later wheat reached the British Isles. Dispersion of cereal grains by wind, animals, and other natural processes was inexorable if slow—perhaps a thousand yards per year on average. Successive plant selections by early farmers led to earlier maturing stands. These native landrace wheats gained a foothold in central Europe and Scandinavia by about 3000 BC via the Danube, Rhine, and Dnieper river valleys. Humanity’s original farmers were most likely women of Neolithic times who tended hearth, home, and hoe while men ranged widely to hunt diminishing herds, first selected grains for kernel size and heads that were less susceptible to normal shattering.

These prehistoric stands of grain were cut by early agriculturalists yielding bone sickles embedded with obsidian blades sharper than later serrated metal versions that date to at least 2000 BC in the Middle Bronze Age. Agricultural folklorist and artist Eric Sloan considered the crescent-shaped sickle to be “the most aesthetically designed implement to have evolved from a thousand subtle variations” over millennia. Anthropologist Loren Eiseley imagines a proto-agrarian scene—likely one of many, when immense prehistoric creatures of horn and hoof still roamed the Levantine valleys, Anatolian highlands, and beyond: “[T]he hand that grasped the stone by the river long ago would pluck a handful of grass seed and hold it contemplatively. In that moment, the golden towers of man, his swarming millions, his turning wheels, the vast learning of his packed libraries, would glimmer dimly there in the ancestor of wheat, a few seeds held in a muddy hand.”