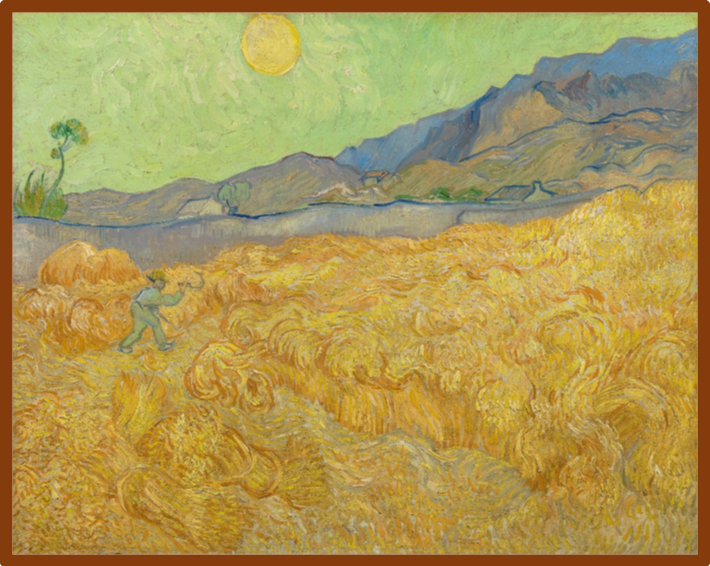

Amidst the mistral winds of June, 1888, Vincent van Gogh painted his Harvest (Wheat Fields) series of ten paintings which provided him opportunity to experiment with color and technique. He worked quickly, “just like the harvester, …intent only on the reaping,” and blended striking hues of gold, copper, and bronze with yellow, red, and brown. The lush expressionistic masterpiece Wheat Field with a Reaper he painted in July 1889, gleams with a swirling sea of grain in impastoed layers of yellow-orange with white highlights seen in many of his Saint-Rémy paintings. A benevolent sun stands against a sky of aquamarine and seems to shine from the canvas uninterrupted by shadow or shade. The view is from the upper story of the building where van Gogh had sought recovery and shows the field’s gray-white boundary wall without any sense of confinement.

Van Gogh, Wheat Field with a Reaper (1888), Van Gogh Museum

Van Gogh wrote of its “vague figure toiling away… in broad daylight with a sun flooding everything with a light of pure gold,” as a modernist expression of “sacred realism” with calm, religious hope in the face of death and his own demise. Association of grain with life suggested humanity’s vulnerability and resiliency in passionate reds and golds composed in balanced synthesis with the greenery and browns of verdant earth. These colors he complemented by mysterious orange and blue tones of the cosmos—a palette strikingly similar to his The Resurrection of Lazarus (1890). In spite of grain’s susceptibility to ruin from fire and wind, or harvest with scythe and sickle, the fields serenely endured as tangible evidence of incomparable beauty, fecundity, and energy of the divine order. The death reaper fulfilled the sower’s purpose in the grand mysterious cycle of life.

Tolstoy’s exposition on aesthetics in What is Art? (1897) embraces a wide range of creative expression from painting and sculpture to literature, folklore, and liturgy. He characterizes their highest forms as conveyance of their makers’ regard for human dignity and the natural world in ways that astonish, mystify, and benefit the common good. That Tolstoy points to Millet, Lhermitte, Gogol, and Pushkin as aesthetic exemplars is significant for their use of agrarian themes to present such universal values. Great painting and writing engender struggle and beauty by depicting meaningful ideas or memorable associations with people and places. Such understanding is at risk in contemporary society at once smart and ignorant. Information technologies can be exploited to distraction for endless browsing and displace contemplation of relationships to the earth and to others.

The characters who inhabit Tolstoy’s stories have heroic capacity, even when cast as loners and losers. They walk familiar paths to work together in the fields and better understand the people and world around them. Among the most stirring moments in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is when landlord Konstantin Levin, who sought the full life of mind, love, and labor, joins a scythe-wielding brigade in an afternoon of great satisfaction: “He… wished for nothing, but not to be left behind the peasants, and to do his work as well as possible.” In a day of tension over progressive approaches to a more sustainable future, considerations of Ruth and Boaz, Barbizon harvesters, and Port William farmers continue to offer meaningful interpretations of land use, technology, and the human prospect.

Praise God for the harvest of farm and field,

Praise God for the people who gather their yield,

The long hours of labor, the skills of the team,

The patience of science, the power of machine.

Praise God for the harvest of conflict and love,

For leaders and people to struggle to serve,

To conquer oppression, earth’s plenty increase,

And gather God’s harvest of justice and peace.

—Brian Wren, “Praise God for the Harvest” (1968)