Greetings blog readers. It was another active summer for us here at Palouse Heritage. We also noticed several other interesting updates that are relevant to our mission of re-establishing heritage grains into our food systems using regenerative practices, so we wanted to highlight a few.

First, Ali Schultheis and other friends of ours at Washington State University announced their Soil to Society pipeline project. The initiative researches strategies necessary to reinvigorate our food system with higher quality, more nutritious whole grain-based foods and making them affordable to all levels of society. We certainly applaud that cause. A very cool aspect to the work is what our friends at WSU’s Bread Lab are doing with the Approachable Loaf Project:

“an affordable, approachable, accessible whole wheat sandwich loaf.” For a loaf to be considered an Approachable Loaf, it must be tin-baked and sliced, contain no more than seven ingredients, and be at least 60-100% whole wheat. It must also be priced at under $8 a loaf, setting it apart from other whole grain, artisan loaves.

Read more about the entire Soil to Society project here.

Another important happening from this past summer was that the respected scientific journal Nature published a paper measuring harmful environmental impacts from agricultural pesticides leeching into ecosystems and freshwater resources:

Of the 0.94 Tg net annual pesticide input in 2015 used in this study, 82% is biologically degraded, 10% remains as residue in soil and 7.2% leaches below the root zone. Rivers receive 0.73 Gg of pesticides from their drainage at a rate of 10 to more than 100 kg yr−1 km−1.

The journal paper is located here. The findings reiterate the importance of our values, which include truly sustainable and regenerative farming practices for the sake of soil and environmental health.

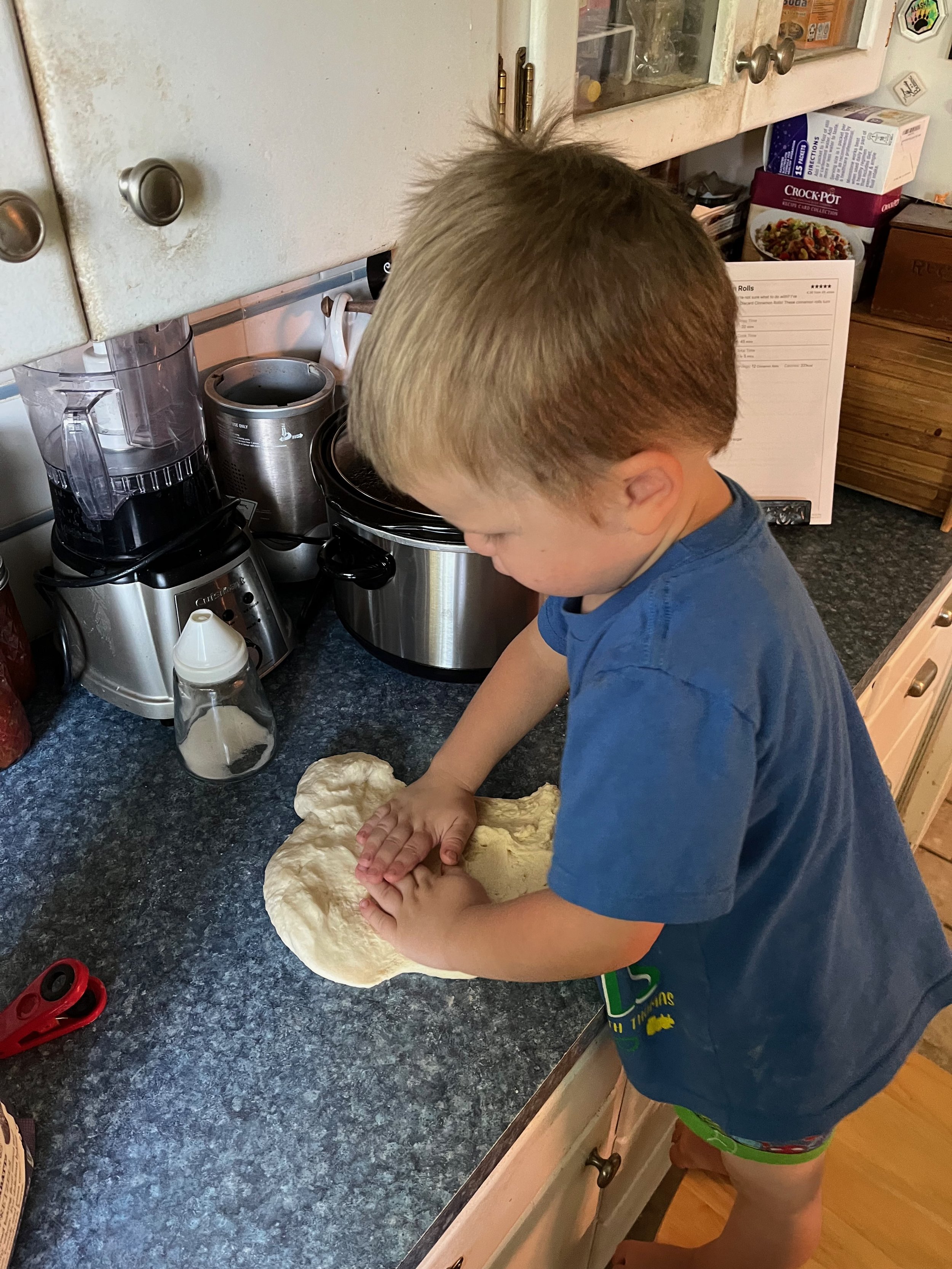

Last but certainly not least, harvest 2023 at our Palouse Colony Farm was a success. Andrew and team had a great crop in spite of low moisture conditions throughout our region. The combination of our farm’s healthy soil along with our hearty landrace grains (and Andrew’s farming talents!) shielded us from the environmental circumstances that significantly reduced average yields around us. Enjoy some photos from harvest, including one of Andrew’s son kneading dough from our grains. Artisan baker in the making!!