Part 1 of this blog post is available here.

Nordic Pancakes and Landscapes

Our Baltic adventure continued with visits to the capitals of Finland, Sweden, and Norway so at every stop we took advantage of tour options to area farms and locations related to rural life and agrarian arts. One gets thoroughly spoiled on cruise ships with food so nicely prepared and abundant along with all manner of entertainment. Our Regal Princess did not disappoint with wondrously rich and crusty European breads and flavorful entrees including buttermilk pancakes and sweet and savory crepes. I’ve come to have special interest in crepes since our Palouse Heritage team has been on the hunt for some time to determine the grain varieties traditionally grown for crepe flour. I’m happy to report that we finally have done so and that next season we will be harvesting our first (though small) crop of Yellow Breton wheat. We learned that buckwheat was customarily used for savory crepes.

Regal Princess Buttermilk Pancakes topped with Strawberries

A special highlight among the Scandinavian stops was a visit to Oslo’s Norwegian Folk Museum, which is a living history park similar to Germany’s Hessenpark near Frankfurt with some 160 historic structures divided among nine areas representing the country’s principal cultural regions. Since Mom’s Sunwold/Anderson ancestors hailed from the scenic Hallingdal Valley northwest of Oslo, Lois and I headed to the park’s restored Hallingdal Village and found not only several 18th century log homes with grassed roofs, there was also a substantial threshing barn and granary. I marvel at the all the effort that must have gone in to deconstructing these and the park’s other many old buildings and then transporting them and reconstructing them here. Walking into the old barn impressed on me the original meaning of the term “threshold” since the entry way had the well-worn raised board that ensured the precious grain flailed (threshed) inside remained inside the building and was not lost outside. Inside the barn were old photographs from Hallingdal showing families at work in fields from long ago fashioning and drying grain sheaves, and flailing and winnowing (cleaning) grain inside the barn. It crossed my mind that those pictured might well have been some distant kin.

Norsk Folkemuseum Hallingdal Village Threshing Barn and Granary and Winnowing

A few minutes’ walk found us entering the park’s restored village of Trøndelag where Lois and I encountered a crowd of enthusiastic children with their parents waiting to enter a long kitchen where a pair of the park’s many workers playing the part of an village inhabitant labored over a hot fire to prepare delicious whole wheat lefse “pancake-bread.” These two ladies spoke perfect English and offered substantial samples slathered in butter and honey which may have accounted for the long line and delighted kids. I knew of lefse because of regular family visits in my youth to our beloved Norwegian-born Aunt Mary Sunwold in Spokane, a native of Hallingdal who had immigrated to America as child and after some years in the North Dakota and Minnesota had relocated with her family to Spokane, Washington.

But Aunt Mary’s lefse was always made of flour mixed with mashed potatoes so had a very peculiar yet pleasant flavor. When we saw the informative Folkemuseum ladies working away on the next batch without any potatoes in sight I asked about their recipe. They laughed and told us that potatoes were commonly used for “poor man’s lefse,” and that most folks preferred it made from wheat flour. Since our clan certainly came from peasant stock, I can understand Aunt Mary’s preference for potato lefse but certainly found this “new old” recipe to be delicious, and nicely sweetened with honey and butter.

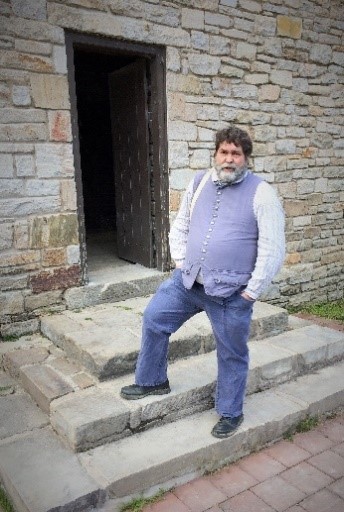

Richard the Trøndelag Rye Field Scarecrow and Baking Lefse, Norsk Folkemuseum

Our culinary historian hosts kindly shared their traditional wheat flour lefse recipe with us which I present here as given to us so will take some conversion from metric to English measure:

INGREDIENTS: 1 kilo wheat flour, 2 eggs, 250 grams sugar, 125 melted butter, ½ liter buttermilk, 1 teaspoon baking powder. DIRECTIONS: Mix eggs with sugar and butter, and stir into the milk. Mix the baking powder with some flour into the blend. Mix with enough flour so the dough is easy to roll flat. (May use barley flour for easier rolling.) Bake on griddle or in a dry frying pan. May be stored in the freezer. Serve with butter, sugar, and cinnamon on top.

The early nineteenth century’s foremost Scandinavian landscape artist was Norwegian Johan Christian Dahl (1788-1857), a native of Bergen raised in poverty who studied in Sweden and Denmark, traveled widely in Switzerland and Italy, and created most of his art in Germany. Dahl’s mature oeuvre represented a synthesis of academy training in Copenhagen in the emotional power of the great Dutch Master grand landscapes with the Naturalism for which Dresden had become famous by the 1820s and where Dahl lived continuously from 1818. Throughout his experiences across the continent, however, Dahl returned recurrently in his art to interpretation of the northern landscapes of his native land with dazzling oils and attention to detail as seen in such canvases as The Fortun Valley (1842) and Hjelle in Valdres (1851). Nestled at the head of narrow Lake Oppstynsvatnet one hundred miles northeast of Bergen, scenic Hjelle in late summer offered an ideal setting for the artist to express the beauty of the countryside and moral virtue of rural folk in a time of rising Norwegian nationalism. The spectacular Hjelle view rendered in Dahl’s meticulous tiny strokes depicts a golden brown field of upright sheaves that seems to glow between a row of village structures to the right with deep blue lake and emerald-clad mountain slopes in the background.

L A. Ring, The Harvester (1884), Oil on canvas, 74 ¾ x 60 ⅗ inches, National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen

Dahl’s most ardent disciple, Thomas Fearnley (1802-1842), met his mentor in 1826 during one of Dahl’s trips to his homeland, and studied with him in Dresden from 1829 to 1830. Unlike Dahl, Fearnley returned to Norway following his studies in Germany to reside there permanently from 1838. Among his many naturalistic rural scenes are Haystacks, Rydal, Cumbria (1838) and View from Romsdalen (1838) that show harvesters strolling throughrolling fields of ripened grain in the fabled coastal valley northwest of Hjelle. The views express Rousseau’s Enlightenment concept of the intrinsic nobility of country people who live apart from the decadent influences of urban life. The paintings of Norwegian Romanticist Hans Dahl (1849-1937) evoke similar sentiment and reflect the influence of his warm palette landscape and portrait studies at the Düsseldorf School in the 1870s and ‘80s. Many of his detailed yet fanciful paintings rendered in fine brushstrokes like Norwegian Girl depict farm maidens returning from the fields in colorful national dress.

Nineteenth century Danish landscape art introduced a synthesis of traditional almue folk art motifs with a softly colored naturalism and rural social consciousness for a new Symbolic Realism evident in the evocative paintings of L. A. Ring (1854-1933), Harald Slott-Møller (1864-1930), and Peter Hansen (1868-1928). Ring was among Europe’s foremost landscape artists and in solidarity with rural identity replaced his surname of Anderson with the name of his native village in southern Zealand. Deeply influenced by Millet and Gauguin, Ring’s paintings depict life’s natural cycle in such masterful compositions as The Harvester (1884), for which his brother served as the model, and The Gleaners (1887). Peter Hansen was an influential member of Funen Painters group who withdrew from Academy traditions and gathered on the Danish island of Funen in a new spirit of Realism. Country scenes there and from his travels in Italy inspired his many genre paintings rendered in soft tones of yellow, brown, and blue that included Threshing with Oxen (1904), Harvest (1910), and Winnowing Wheat (1914).

Vasa Family Grain Sheaf Coat of Arms, Contemporary wood sculpture from a 15th century warship, The Vasa Museum, Stockholm

The image of a grain sheaf had long been used throughout northern Europe as a symbol of prosperity and peace as prominently featured in Allegory on Peace Being Crowned by Minerva (1643) by Danish painter Willem de Poorter (1608-c. 1650). Other notable examples include Tsar Peter the Great’s Grand Sheaf Fountain (c. 1720) in the Monplasir Gardens of his grand Peterhof Palace estate overlooking the Baltic Sea near St. Petersburg. Peter designed the fountain base to resemble the wide rounded base of a sheaf with water casting forth from two tiers of jets as if arched stalks of grain. The medieval crest of Sweden’s Vasa dynasty, which derives its name from a term for sheaf, features of a central golden sheaf and crown flanked by two cherubs. The jeweled Royal Order of Vasa which also incorporates the sheaf design was created in 1772 by King Gustav II to recognize outstanding achievement in agriculture and the arts.

![Albrecht Dürer, “Mary in [Grain] Ear Dress” (c. 1515) Randzeichnungen zum Gebetbuche des Kaisers Maximilian I (Munich, 1907)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/577c39f56b8f5bec285fe33f/1497399768321-CFHUQ3CRSFXUKXUVYFHA/image-asset.png)