Contemporary agrarian art and literature offer insightful if complex perspectives on the transformation of such rural landscapes and ways of life. Stories and paintings are elegiac and abstract as well as hopeful, with expressions of agrarian renewal evident in newfound appreciation for regional heritage and stewardship of the land. These considerations juxtapose values related to the natural world with those of private development and global capitalism. There is little to regret about archaic rural prejudices, grinding aspects of exhaustive dawn to dusk farm labor, and highly erosive tillage practices. Small town redevelopment efforts are leading to examine in new ways how local stories and resources might be shared to better contend with shifting labor patterns and demographic change. Harvest bees and church benefits still aid neighbors in times of special need. More broadly, the harvest experience abides with seasonal urgency because of its changeless and necessary provision. The instinct unites humanity worldwide through rituals of planting and harvesting and thanksgiving.

Cultural tensions rise in the wake of climate change, global food security needs, and concern about impacts on soil biomes and wildlife. Establishing balance involves mediation of the ancient urges for veneration and exploitation, and the serious critique of technocratic limits in agricultural improvement. Wendell Berry’s writing offers a fertile field of practical recommendations for how persons living anywhere can apply the useful habits of memory, attention, and reverance to promote the good life. Wendell Berry recognizes the primacy of earth care to support all other human endeavors, and likens this to holy service: “The most exemplary nature is that of the topsoil. It is very Christ-like in its passivity and beneficence, and in the penetrating energy that issues out of its peaceableness. It increases by experience, by the passage of seasons over it, growth rising out of it and returning to it…. It keeps the past, not as history or memory, but as richness, new possibility.”

Earl Roberge, Stalks of Wheat (c. 1960), Franklin County Museum; Pasco, Washington

Whether on a Midwest farm or in a Chicago high-rise, one can live with fidelity to place by learning and practicing the home arts and community building. Family care and homemaking need not require moving “back to the land.” In any setting folks can summon moral courage to eat together, shop locally to support practicioners of local crafts, connect young people to worthwhile endeavors, and affirm the values of environmental stewarship. Policies and practice of self-reliance and promotion of the common good that characterized republicanism in the ancient world are relevant more than ever in an era of threatened landscapes, endangered species, and marginalized labor. Environmental ethicist Julie Crouse characterizes Berry’s ongoing literary conversation about these matters as a “sacred harvest” for renewing the common good by promotion of connections among people, landscapes, and spirituality. In the context of farm work for participation in the market economy, or mental work for healthy imagination and discernment, Berry calls the external standard of such endeavors the “Great Economy,” or the “Kingdom of God.” The goal is to promote abiding, abundant harvests and the long term wellbeing of individuals in community.

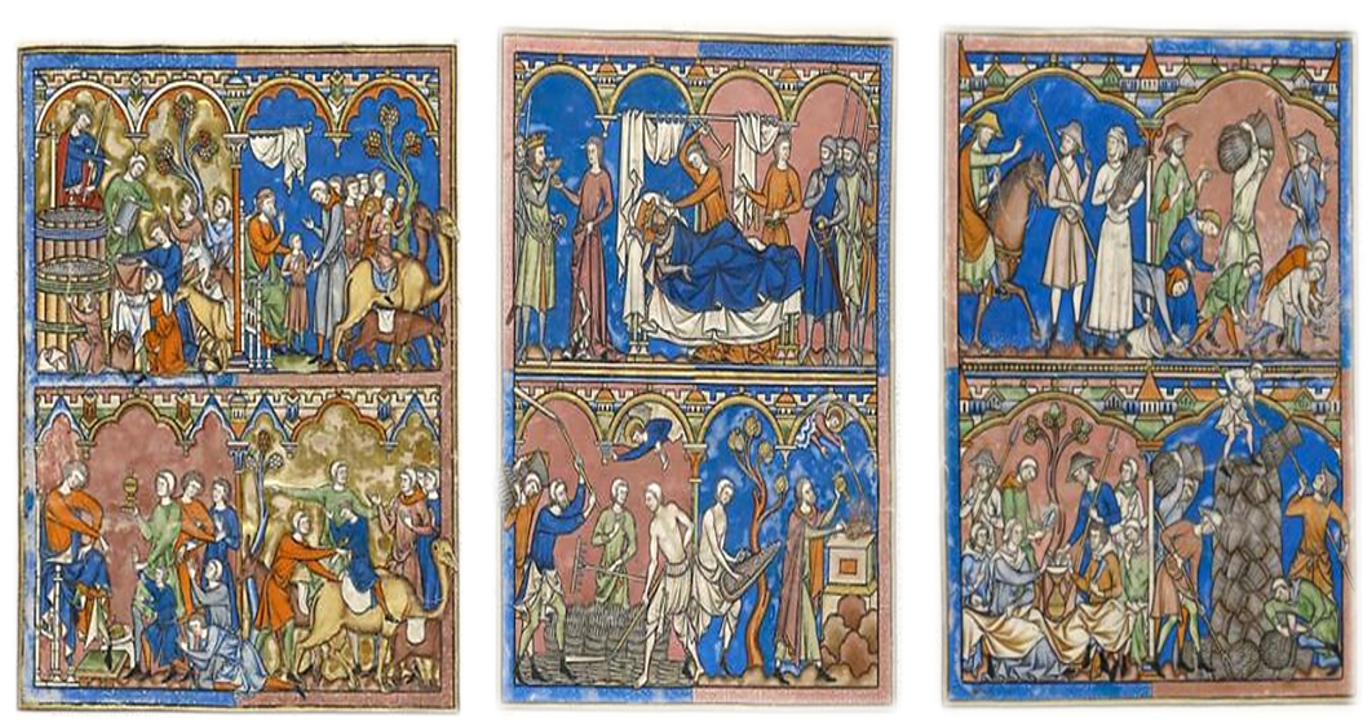

Berry has explored these ideas most fully in his novels and short stories about the Coulter, Catlett, Branch, and other families. They dwell together in imaginary Port William, for which the author’s native Port Royal, Kentucky, serves as a touchstone. The place is not a utopian metaphor as its residents navigate with failure and success through cross-currents of old ways and modernity’s encroachments and benefits. In “That Distant Land” (1965), a rural neighborhood crew gathers for tobacco harvest in the sweltering August heat, and Berry casts a scene that resembles field laborers of ancient times: “They drove into the work, maintaining the same pressing rhythm from one end of the row to the other, and yet they worked well, as smoothly and precisely as dancers. To see them moving side by side against the standing crop, leaving it fallen, the field changed, behind them, was maybe like watching Homeric soldiers going into battle. It was momentous and beautiful, and touchingly, touchingly mortal.” The classical allusion is not incidental. In “The Agrarian Standard” (2002), Berry invokes lines from Virgil’s Fourth Georgic about “an old Cilician” who cares for a small plot of land that produces abundantly because of an ethic “rooted in mystery and sanctity” that values giving back to the health of the soil—an affectionate agarian stewardship for the sake of present and unborn generations.

Mentalities of moderation foster individual identity as well as social cohesion to sustain both culture and soil. In his foreword to Of the Land and the Spirit (2008), an anthology of Walter, Lord Northbourne’s writings on ecology and religion, Berry (like Lord Northbourne) points to perennialist matters of ultimate purpose as expressed by Jesus to, “[S]eek first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness...,” in order to be provided food, drink, and clothing. Berry suggests that mastery of agriculture, husbandry, weaving, and other skills are assumed in this context, and that Jesus demonstrated faith by prayerful service to others in feeding and healing them. In these ways, literary, artistic, social, and vocational endeavors in any age represent harvests in which anyone can participate.

Johann Raphael Wehle, And They Followed Him (detail, 1900), Lithograph on cardboard, 4 x 6 inches, Columbia Heritage Collection