The Georgic World and Roman Expansion

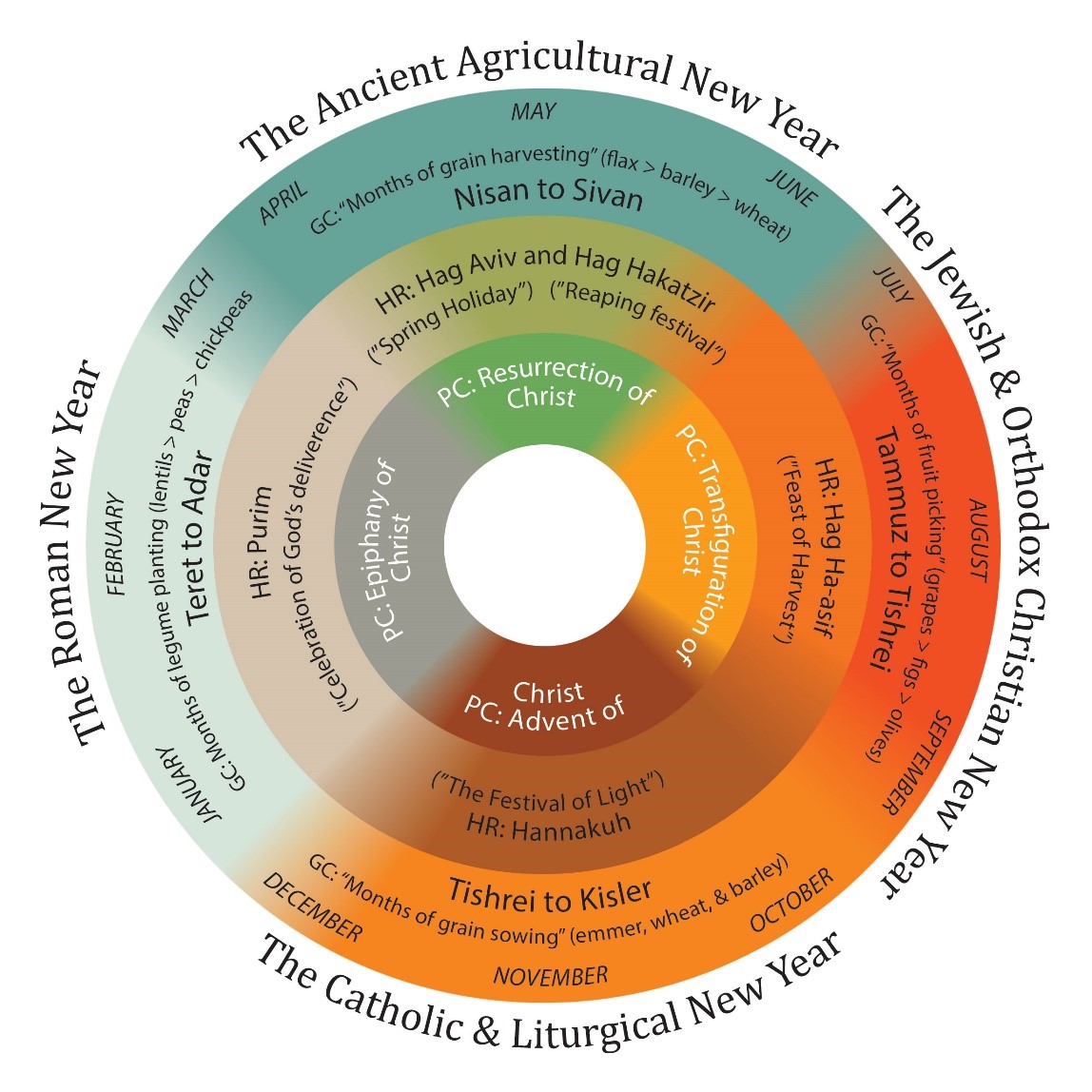

The Latin root of Ceres’ name, ker, is cognate to “cereal,” “create,” and “crescent,” while the name “Demeter” also relates to “matter” and “meter.” The latter word suggests the natural rhythms of nature less known since the industrial age, yet inexorably evident in Time’s harvest of human life. The implicit hope of death’s renewal for the new generation, therefore, was not a grim prospect to ancient peoples in spite of its subsequent medieval association with a fearsome scythe-bearing reaper. The Roman god Saturn was sometimes depicted with scythe or sickle because of his associations with agriculture, generation, and renewal, and was celebrated from December 17 to 23 in the major Roman festival Saturnalia preceding the winter solstice.

In Naturalis Historia, Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) notes that “numerous grains” were raised throughout the empire which “received their names from the countries where they were first produced.” He evaluates grain by weight with the Roman average being approximately three pounds per quart, and agricultural historians calculate average yields to have been about fifteen bushels per acre. An experienced adult harvester could reap about one-half acre, or slightly less, with a sickle in a backbreaking twelve- to fourteen-hour day. This grueling regime was carried out for weeks in the scorching heat and the method remained basically unchanged until the advent of the long-handled scythe in Western Europe during the late Roman era. But the broader blade of the scythe and greater resistance from cutting wider swaths meant scything was generally, but not exclusively, the work of able-bodied adult males. Reaping up to one and one-half acres per day was considered average under favorable circumstances. But use of the more violently swung scythe resulted in the loss of up to ten percent of the precious grain as ripe, brittle stalks are subject to shattering. For these reasons, use of sickles by both men and women for harvesting high value grains like wheat and rye was widespread throughout the world until the twentieth century.

The vital, labor intensive harvesting operations in ancient times required overwhelming participation by the masses. Worker numbers are difficult to determine with precision, but historians estimate that up to one-half of the population engaged directly in the seasonal processes of reaping, binding, and carting, with perhaps forty percent more involved for longer periods in the tertiary operations of threshing, winnowing, and storage. Indeed, provisioning the populace was the preeminent task of any people and a chief preoccupation of their leaders in Egypt, Greece, Rome, and beyond. According to the Elder Pliny, Italian and Boeotian (Ukrainian) wheats rated “first rank,” followed by Sicilian and Alexandrian. “Third rank” wheats included Thebian and Syrian. Pliny also favorably rated Greek wheats from Pontia, Strangia, Draconia, and Selinusium, and noted production in Cyprus, Gaul, Chersonnesus (Crimea), Bactria (Afghanistan), and the Balearic Islands. Cereal grains contributed significantly to the ancient Roman diet which was generally high in plant protein and carbohydrates. The cultural significance of barley and wheat is evident in numerous copper, silver, and gold coins from the ancient world that depict these grains.

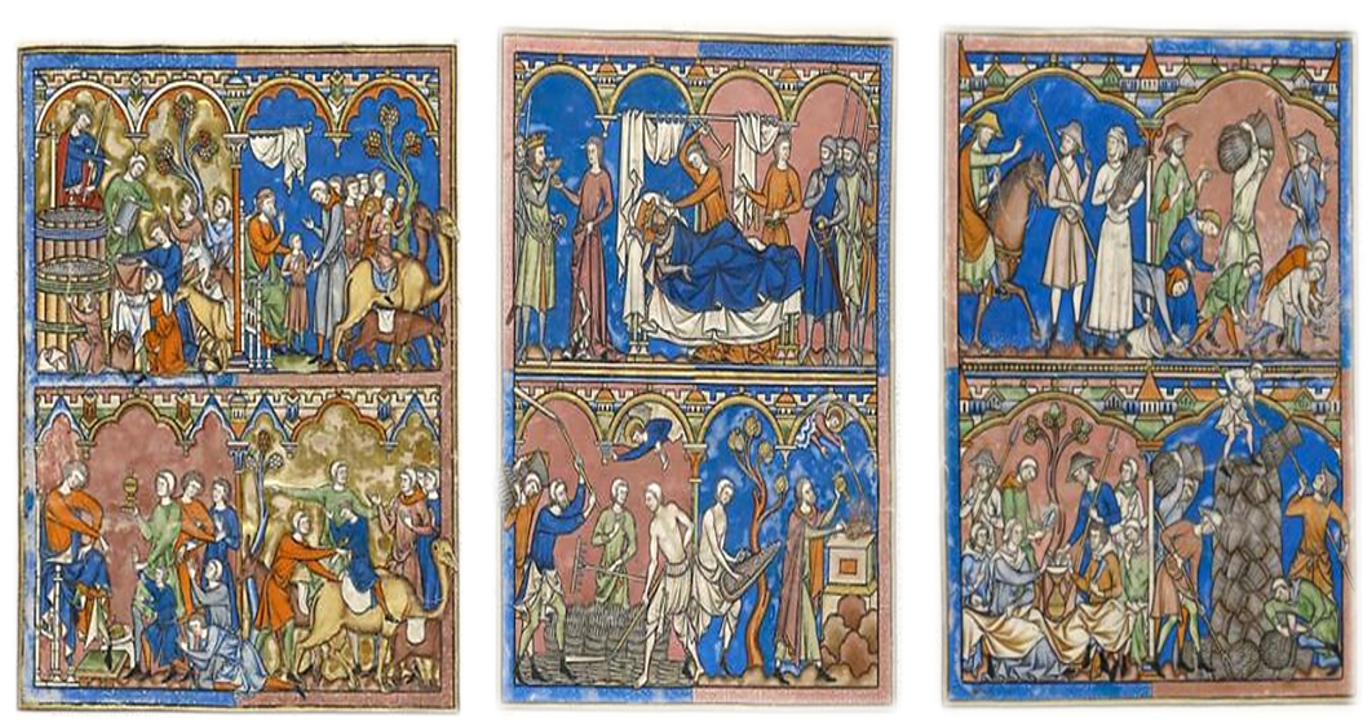

The Italian farro grains emmer and spelt were staples of the legionnaires who made nutritious soups from the cracked kernels and likely spread it and other Roman varieties throughout the empire. The Latin term “gladiators,” hordearii, literally means “barley eaters” since they subsisted on high energy foods like barley, oatmeal, and legumes. Roman legionaries were routinely outfitted with sickles in order to procure their livelihood throughout the far flung empire, and probably used them more often that their weapons. The helical frieze on Trajan’s Column in Rome (c. 110 AD) features a dynamic group scene (plates 291-292) of soldiers in full uniform harvesting waist-high grain with prodigious heads. (The English word “harvest” is derived from German Herbst (autumn), which descends from a root shared by Latin carp- [“to gather”] and Greek karpos [“fruit”]. “Harvest” in the sense of reaping grain and other crops came into vernacular use during the medieval era of Middle English. Likely due to the light color of a wheat kernel’s interior endosperm, the word “wheat” in many European languages meant “white,” as with Old English whete, Welsh gwenith, and German weizzi.).

Trajan’s Column Harvest Scene (c. 110 AD); Conrad Cichorius, Die Reliefs der Traiansäule (Berlin, 1900)

Roman poet Virgil’s epic the Georgics (c. 30 BC, from a Greek term meaning “farmer” or “agriculturalist”) carries the passionate message that human culture is inextricably bound to the culture of the soil. The influence of Virgil’s 8th century BC Greek predecessors Homer and Hesiod is apparent in the poem. Hesiod’s didactic Works and Days is a masterful poetic admixture of practical farmer’s almanac with ethical maxims and superstitious sayings intended to benefit an indigent brother. The descriptions are rich with depictions of everyday country life that shed light on a vast array of ancient trivia ranging from agrarian diets (“eight-slice wheat loaf” and “barley bread made with milk”) to harvest labors (“sharpen your sickles, …exhausting summertime has come”). As with Homer and Hesiod, like most other substantial works in Greek and Latin, Virgil’s meter is dactylic hexameter but his hymn displays a perfection of image and style unprecedented in ancient literature.

The Georgics’ opening line makes clear one of the work’s principal themes—“What makes the grainfield smile…,” followed by a wondrous narration of forces—both natural and supernatural, that influence annual harvests. Although a hard-working farmer can contend with choking weeds, granary mice, and to some extent drought, Virgil (70-19 BC) also tells of destructive winds and rain, and plundering armies that are beyond any conscientious laborer’s control. The Georgics is no pastoral lauding the life of contemplation. Pastoralism in art, and to greater extent in Virgil’s Eclogues, is generally characterized by idealized natural settings devoid of laborers, or at most showing herders who passively oversee livestock. A rural idyll similarly expresses such experience through a short story or poem. Virgil, however, seeks through his own deep acquaintance with the countryside, crops, and convulsions of Roman Republic politics to relate the heroic virtues of diligence and frugality against the vagaries of private life and public affairs. A native of Italy’s fertile Po valley, Virgil knew first-hand the challenges of Sabine peasant life known by the region’s small landholders (colonui) as well as the realm of responsibly managed and intensively farmed villa estates.

Antoine Watteau, Ceres (1717/1718); Oil on canvas, 55 ¾ x 45 ½ inches; Samuel H. Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.

Georgics relates an irrepressible conflict of mythic proportions between the peaceful bounty of Saturn’s Golden Age under siege by Jupiter’s menacing minions in a “Jovian Fall” that would revert humanity from pastoral balance to wilderness. The Augustan era’s civil wars resulting from political and military contests between Julius Caesar and Pompey left vast numbers of Romans landless through no fault of their own. The Georgics further represents an earnest call of both homecoming and longing in spite of ruthless forces conspired against such return and oblivious to the primacy of land care. The three great Roman agricultural prose writers—Cato (De Agricultura), Varro (De Re Rustica), and Columella (Res Rustica), treat farming in didactic terms while Virgil’s masterful composition is also a love song for native soil and the ordinary folk who labor upon it.

The four books of the Georgics cover a range of agricultural topics familiar to Roman farmers—field crops (I), trees and vines (II), livestock (III), and beekeeping (IV). Each functions as an essential component in an integrated, holistic approach to soil fertility and production involving cereals, fruits, and livestock. Only zealous attention to details like soil condition, preparation of the threshing floor, and regular tasks like hoeing offer some prospect of a prosperous household and foundation for civil society. The emblems of Virgilian verse—plow and wain and harvest, wonderfully relate agrarian experience as a restorative moral obligation. Prospect of the beneficial labor and contemplation they represent to foster kindness, moderation, and peace of mind in the face of life’s challenges would inspire artists and authors for generations to come.

(160-165)

“Now to tell

The sturdy rustics’ weapons, what they are,

Without which, neither can be sown nor reared

The fruits of harvest; first the bent plow’s share

And heavy timber, and slow-lumbering wains

Of the Eleusinian mother, threshing-sleighs….

And drags, and harrows with the crushing weight;

Then the cheap wicker-ware of Celusius old….”

(313-318)

“When Spring the rain-bringer comes rushing down,

Or when the beards of harvest on the plain

Bristle already, and the milky grain

On its green stalk is swelling? Many a time,

When the farmer to his yellow fields

The reaping-hind came bringing, even in act

To lop the brittle barley stems, have I

Seen the all the windy legions clash in war….”