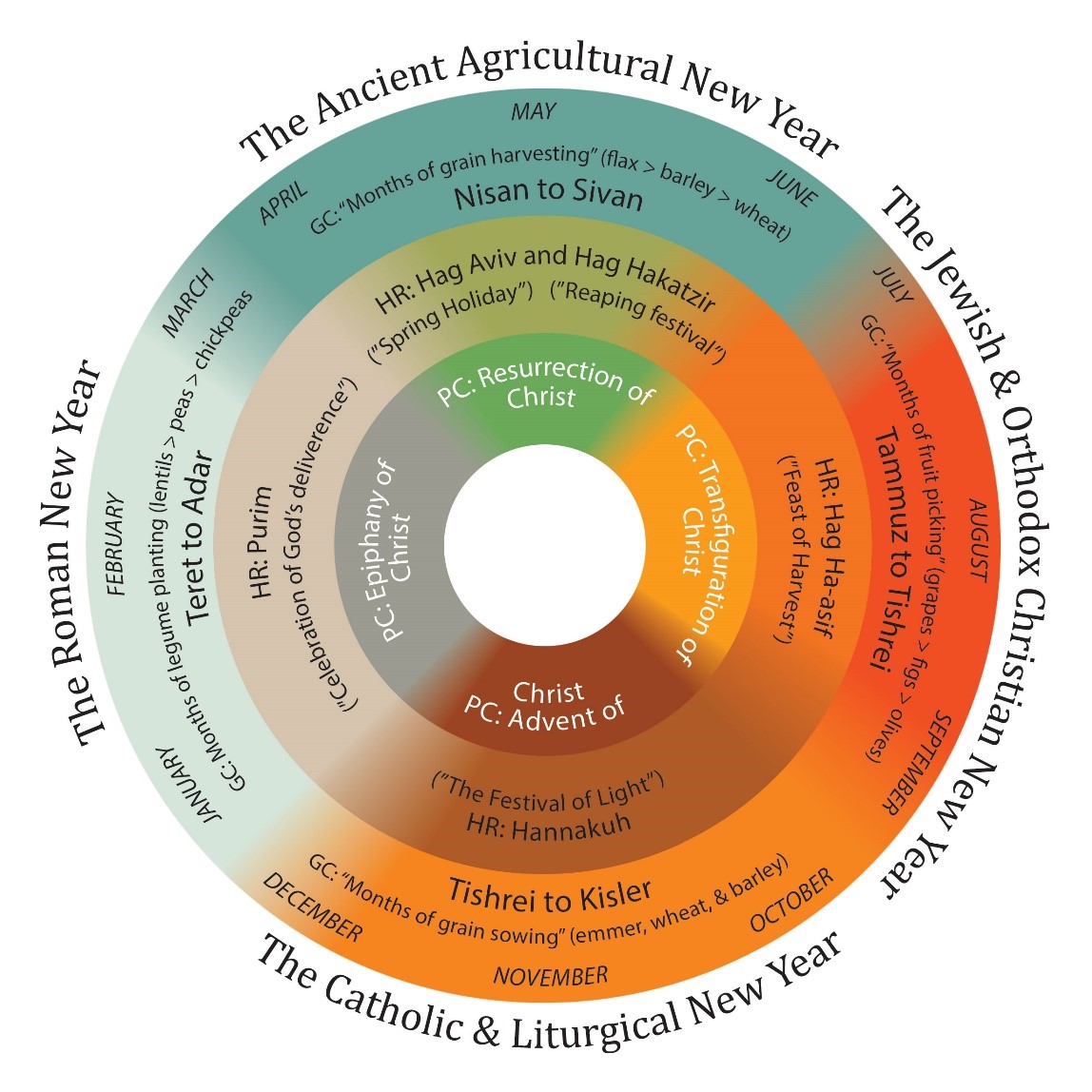

Few words conjure up richer connotations of summertime, country life, and abundance than harvest. During the past three weeks we have commenced harvesting our Palouse Heritage grains and are pleased to report excellent quality and yield. Ever being interested in matters of origin, I decided to investigate the derivation of the word “harvest,” and learned that it is derived from German Herbst (autumn). That word in turn descends from a root shared by Latin carp- (“to gather”) and Greek karpos (“fruit”). “Harvest” in the sense of reaping grain and other crops came into vernacular use during the medieval era of Middle English.

Palouse Heritage Yellow Breton Wheat Harvest near Connell, Washington (July, 2018)

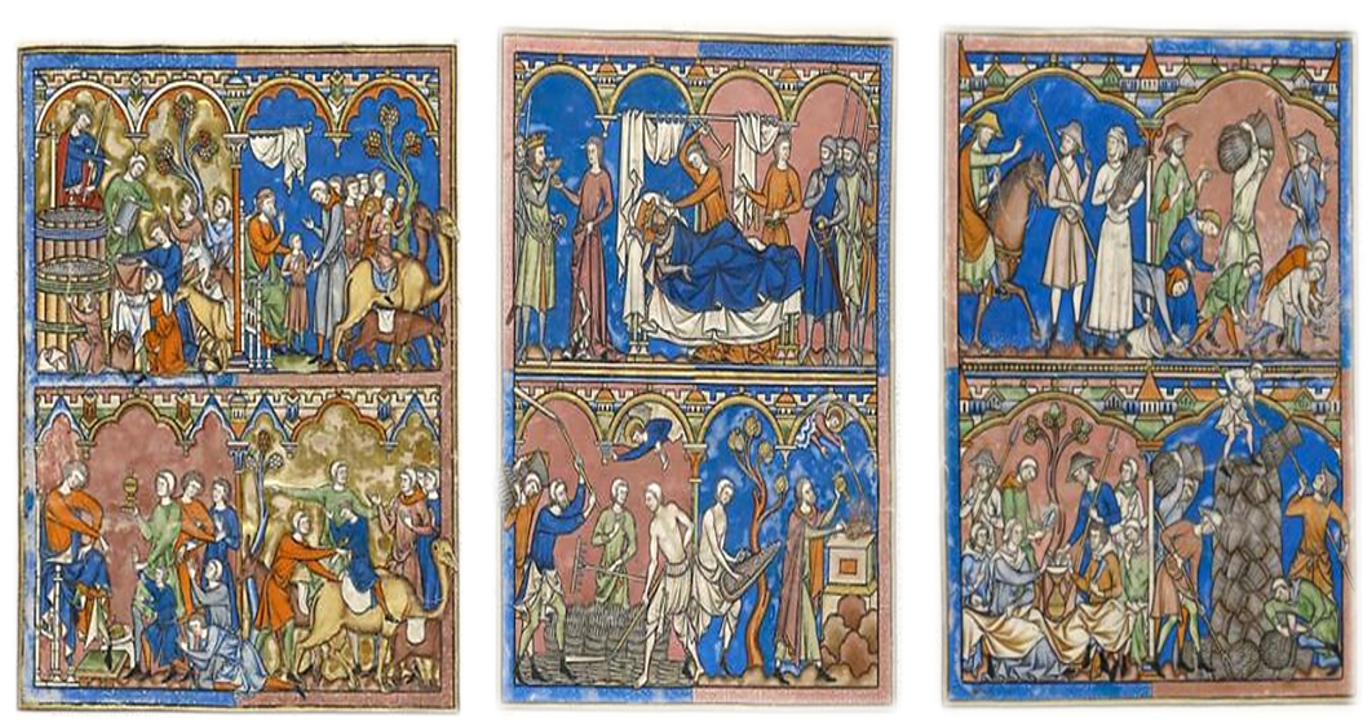

Likely due to the light color of a wheat kernel’s interior endosperm, the word “wheat” in many European languages meant “white,” as with Old English whete, Welsh gwenith, and German weizzi. The Latin term “gladiators,” hordearii, literally means “barley eaters” since they subsisted on high energy foods like barley, oatmeal, and legumes. Roman legionaries were routinely outfitted with sickles in order to procure their livelihood throughout the far flung empire, and probably used them more often that their weapons. The helical frieze on Trajan’s Column in Rome (c. 110 AD) features a dynamic group scene of soldiers in full uniform harvesting waist-high grain with prodigious heads.

These days we don’t need to rely on sickles and legionnaires to bring in the crop. Good friends like Brad Bailie of Lenwood Farms near Connell, Washington, raise bountiful crops of organic Palouse Heritage varieties like Crimson Turkey and Yellow Breton. The latter is a soft red variety native to the northern France where for generations it was used for the prized flour essential for flavorful crepes. Farther to the northeast in the vicinity of Endicott, Washington, our longtime friends Joe DeLong and Chuck Jordan are harvestings stands of Palouse Heritage Red Fife, a famous bread grain originally from Eastern Europe, Sonoran Gold wheat, and Scots Bere barley that has become one of the most sought-after craft brewing malt grains.

Although there are some variations in climate and soil across the inland Pacific Northwest, this fertile region lies within the great arc of the Columbia River’s “Big Bend” easily identified on any map. While reading through some old newspapers recently I encountered the following poem titled “The Big Bend” by Louis Todd that was published in 1900. Little else is known about Todd’s life, but his literary expressions here make it clear he greatly appreciated this land of harvest time “golden splendor.”

No other river to the ocean

Will a tale like thine unfold,

Of the wealth seen in thy travels;

Of the wealth thy borders hold;

For thy thoughts the grandeur bear,

And thy breath the sweetness breathes,

Of the boundless fields and forests,

Of the richly laden trees.

And there grows within thy roaring

All the fairest of the vine;

Luscious fruits in clusters hanging

From the north and southern clime.

Great fields of wheat in golden splendor,

Waving like a mighty sea,

Holding safe their precious treasure

’Till the grain shall ripened be.

Where nature works with freest hand,

Builds her greatest work of art,

Will the feeble life of man

There most smoothly play its part.

Oh, leave the dreary course you travel,

Spurn the rocky path you go,

Join again your life with Nature,

Where the fragrant flowers grow.

Palouse Heritage Red Fife Wheat Harvest (July, 2018)