Katherine Nelson’s reputation as artist, thinker, and friend of rural ways long preceded my meeting her several years ago. She had lived in the Spokane area in the 1990s and fallen in love with the rolling grainlands of the Palouse Hills. Although now living in Washington, D.C., Katherine has regularly traveled across the continent since the early 2000s to capture the Palouse’s summertime chiaroscuro of swirling slopes, saddles, and swales. She happened upon our cousin Tom Schierman’s “oasis” in the hills near the hamlet of Lancaster several miles north of our Palouse Colony Farm, and through Tom we came to be acquainted. Katherine traces threads of her fascination with the region to her diplomat father’s interest in Turkish rugs: “I remember their textures and shapes which influenced my affection for rolling landscapes. The Palouse is a tapestry of woven connections among seasons, fields, and people. The effect is thoroughly spiritual and provides a place of reflection, solace, and beauty that overcomes the noise of the outside world.”

To emphasize the effects of light for line and shadow, Katherine works entirely in black-and-white which evokes heightened awareness of layering, texture, and movement. “My ‘Portraits of the Palouse,’” she explains, “are metaphors for the human prospect. ‘Harvests’ to me are exhibitions that depict the land as hallowed space through views of heritage farm architecture and landscape vistas. Implicit rural values relate to the natural environment, hard work, and community, and are relevant anywhere.” This coming July 14, Katherine’s work will be featured at Art Spirit Gallery in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, and I’ll be on hand to give a talk about her remarkable art at 10 a.m. that morning.

Katherine Nelson, Palouse Harvest Oasis (2015), Charcoal on paper, 22 x 30 inches, Collection of the Artist

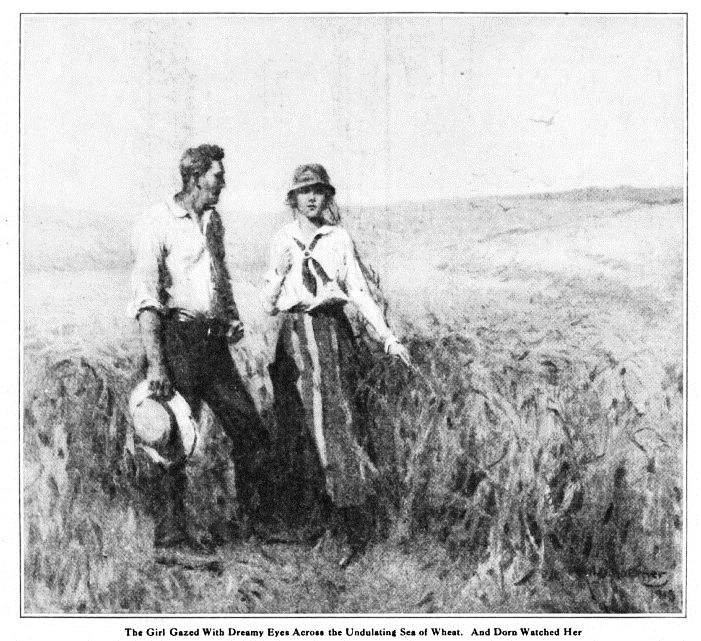

Another artist whose agrarian paintings recently caught my eye is Hal Sutherland (1929-2014). He became enamored with rural themes late in the 1980s after a distinguished career as a Hollywood animator and television producer. Born in Massachusetts amidst the onset of the Great Depression, Sutherland moved to the West Coast in the early 1940s and after military service studied at the Art Center School of Design in Los Angeles. His skills and study led to work at Disney and he eventually acquired his own production studio. Sutherland overcame any limitations from color blindness by developing a color-coded palette and experimented with unusual color combinations. In 1974 he relocated to a small farm near Bothell, Washington, devoted the rest of his life to painting and became president of the American Artists of the Rockies Association.

Hal Sutherford's Wheat Harvest (c. 1985)

Although long interested with Western Indian and history themes, Sutherland turned his attention to landscapes late in his career and began touring the American countryside in the 1980s. “…[T]here’s a tremendous void regarding American farmers and the unbelievable hardships they endured,” he stated in a 1989 Art of the West interview. “It’s my hope to capture as much as I can so their stories can be remembered It’s hard to imagine the severity of the struggle confronted daily by those folks. …[Humor] helped carry them along in their various dreams of a new start in life, as they carved out the heartland of this country for generations to come.” In this spirit Sutherland painted with detailed realism such farm scenes as Wheat Harvest (c. 1985) with a team of sickle-wielding men and women binders, and a returning farmer and work horse in Day’s End. Regarding the latter, he commented, “Rewards are often meager for hard labor such as farming. But, after a long day struggling in the fields, it had to bring tremendous satisfaction to have accomplished the task and to be rewarded with one of God’s painterly skies as you headed homeward.”