This post is the first of a three-part series about Zane Grey, the father of the modern Western novel, who spent time in Eastern Washington in the early 1900s to write his agrarian-themed novel The Desert of Wheat.

For many years I kept a copy of Zane Grey’s novel, The Desert of Wheat (1919), on my bookshelf. I confess it was mostly there because the title had piqued my hope that the famed Western author might have once turned his attention away from Southwestern cowboys to farmers in the Northwest. A few pages into the book confirmed its setting to be on the Columbia Plateau. But encounters on its opening pages with “motor-cars” and labor organizers led me to set it aside in favor of what I thought might be more interesting reads. Only in recent weeks did I return to the book after realizing that Grey had composed it amidst the convolutions of American involvement in World War one hundred years ago. So I pulled it off the shelf again and this time found myself immersed transported through compelling prose to a remarkable time that I found had high relevance to many issues of our present day.

Best-selling author and conservationist Zane Grey (1872-1939) is considered the father of the modern Western novel. He wrote eighty books with nine selling over 100,000 copies in their year of initial publication, including the quintessential Western classic Riders of the Purple Sage (1912) which became a million-seller. Even today sales of his many works typically reach 500,000 copies annually. Grey’s novels and some 300 short stories were known for idealizing the American frontier spirit with archetypal characters inhabiting moral landscapes who exemplified the Code of the West—integrity, friendship, loyalty. British poet John Masefield and Ernest Hemingway considered his writing praiseworthy and others compared allegorical storylines laden with struggle and mystery to the ancient Beowulf saga and Star Wars science fiction trilogy. Though some critics found Grey’s plots to be formulaic, several of his works ventured beyond worlds inhabited by cowboys and desperados to explore contemporary issues, and human influence on landscapes.

Zane Grey’s The Desert of Wheat first appeared in a series of articles published in May and June, 1918, issues of The Country Gentleman

Grey and his wife, Dolly, journeyed from their home in Pennsylvania to the Pacific Northwest during the summer of 1917 and traveled through eastern Washington in July. That same tumultuous month Alexander Kerensky was named premier of the Russian provisional government after revolutionaries toppled the Romanov monarchy, and a major German World War I counter-offensive commenced on the Eastern Front in Galicia. Grey closely followed world events through newspaper reports sought to incorporate their impact on American national life into his writing. He had been encouraged by The Country Gentleman editor Benton Currie to compose an agrarian-themed story for serialization the following year.

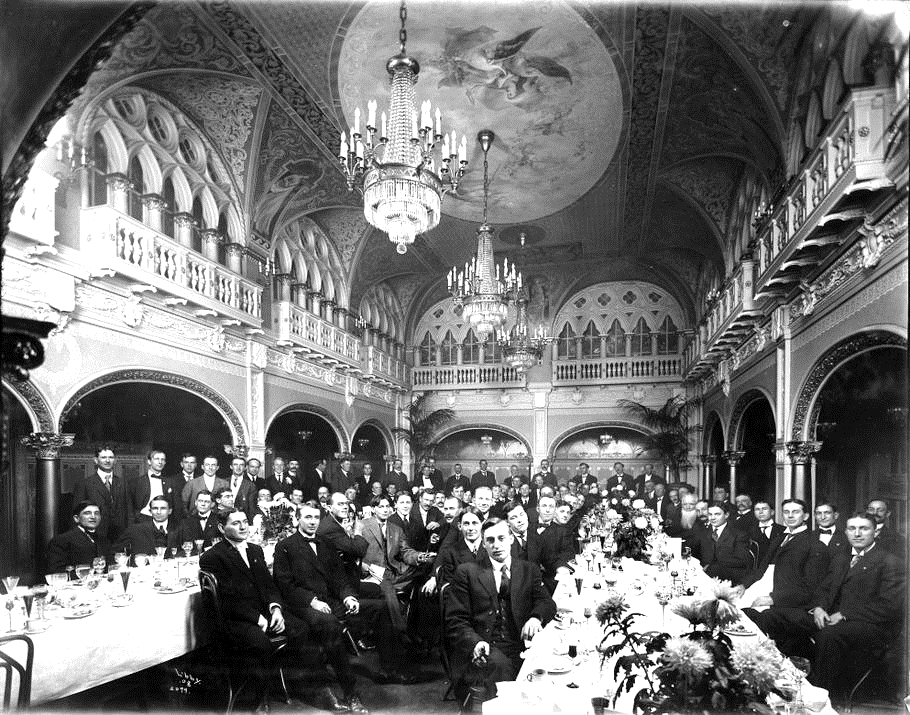

Davenport Hotel Hall of Doges, Spokane, c. 1915, Washington State Historical Society

While attending a Chamber of Commerce luncheon in July at Spokane’s opulent Davenport Hotel, Grey and A. Duncan Dunn, regent of the state’s agricultural school in Pullman, discussed the plight of the region’s farmers since Northwest grain markets and labor unrest seemed highly related to unfolding international events. Inspired in part by events in Russia, the Industrial Workers of the World (“Wobblies”) sought to organize itinerant harvest laborers throughout the wheatlands in order to hold out for raises from two to three dollars for a customary ten-hour day of intense physical labor tending the annual threshing operations. The Wobblies were strongly opposed by farmers on economic grounds, and many throughout the country considered their socialist leanings a threat the moral and political order. The inland Pacific Northwest was also heavily populated by immigrant farmers of German ancestry from central Europe and Russia. Grey’s story would also explore the tensions within families and communities created by complex relationships between heritage and nationalism.

Zane Grey, The Desert of Wheat Manuscript Opening Lines (1917), Library of Congress

Grey’s “The Desert of Wheat” would first appear in several installments of The Country Gentleman in the spring of 1918, and Harper’s published the first of numerous printings in book form in 1919. His earlier works had been known for vivid descriptions of action and environment, as well as respectful inclusion of Native Americans and minority cultures. This new work appealed to both reviewers and the general public, and opened with lines inspired by his summertime journey across the Columbia Plateau’s vast farming district: “Late in June the vast northwestern desert of wheat began to take on a tinge of gold, lending an austere beauty to that endless, rolling, smooth world of treeless hills…. The beauty of them was austere, as if the hand of man had been held back from making green his home site, as if the immensity of the task had left no time for youth and freshness. Years, long years, were there in the round-hilled, many-furrowed gray old earth.”

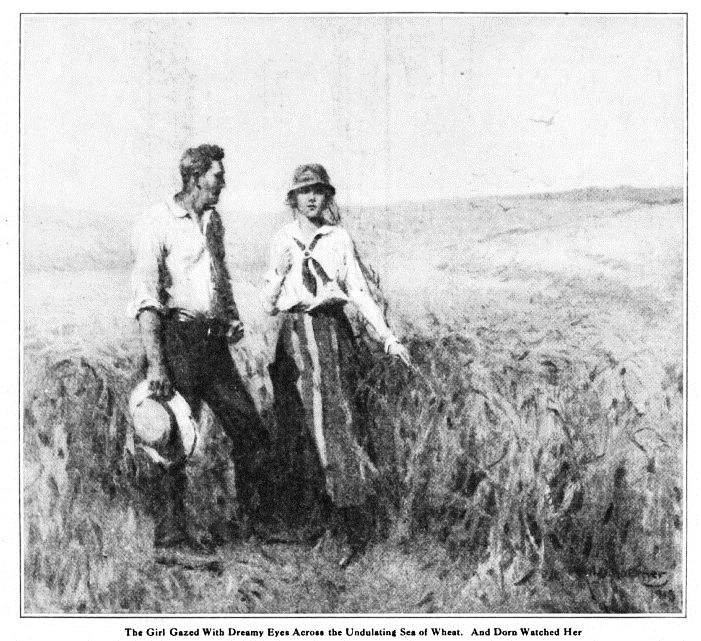

Right: W. H. D. Koerner, “The Undulating Sea of Wheat,” Country Gentleman Magazine (May 14, 1918)

Through dialogue about Bluestem and Turkey Red wheats and rattling threshers under the hot harvest sun, the story lauds the hard work and struggles of taciturn Kurt Dorn, son of an elderly German immigrant farmer. Young Dorn faces drought, blight, and the elements in order to support his father, and experiences World War I prejudice and rural labor strife. Although Grey’s characters are not typically prone to mystical reflection, Dorn and protagonist love interest, Lenore Anderson, ponder the significance of change in their own relationship, his enlistment and brutal experience of European battle, and deeper meanings of wartime damage to culture and conviction. As do few other books in Grey’s considerable corpus, The Desert of Wheat exemplifies his lifelong compulsion to express “Love of life, love of youth, [and] love of beauty.” Dorn and Anderson’s dialogue further attest to the wastefulness of war and Grey’s own ambivalence over conceptions of patriotism and heroism. Literary historian Christine Bold characterizes Lenore Anderson as the personification of humanity’s spiritual core—a “Western version of Ceres,” and like waving heads of grain frequently described she symbolizes renewal amidst an odyssey of life, loss, and land.